The sprawling canvas of Killers of the Flower Moon unfurls against the backdrop of early 20th-century Midwestern history, a tapestry woven with echoes of contemporary political malaise. Martin Scorsese, renowned for capturing the gritty essence of American life, takes a departure from the bustling streets of Gangs of New York to the desolate prairies where America, in this narrative, meets a slow death. The film, inspired by David Grann’s disquieting non-fiction bestseller, peels back the layers of history in Osage County, Oklahoma, revealing a dark underbelly of greed, exploitation, and the banality of evil.

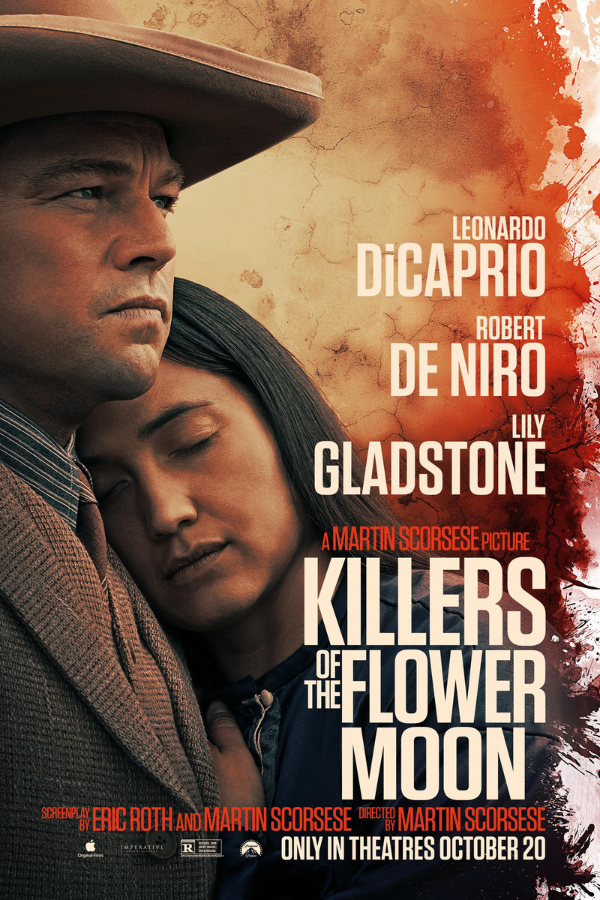

The Osage nation’s land, once consecrated and now bursting with oil, turns its members into some of the richest individuals on the planet. However, the newfound wealth becomes a curse as a complex web of white profiteering takes root alongside the oil derricks. “King” William Hale, played by Robert De Niro, emerges as a bespectacled tyrant who, under the guise of philanthropy, orchestrates a reign of terror to inherit the “head rights” for the Osage oil wealth. Leonardo DiCaprio steps into the shoes of Ernest Buckhart, a proto-Jordan Belfort type, whose love for money becomes a chilling mantra amid the unfolding tragedy.

The film’s tone aligns more with Scorsese’s contemplative works like Kundun or Silence, contrasting sharply with the hedonistic excesses of The Wolf of Wall Street. It critiques capitalist exploitation at a sociopathic level, where human suffering is an acceptable cost for long-term gains. The film refrains from glorifying the immoral deeds of its characters, opting instead for a more objective perspective that centers on the struggles of the Osage.

However, as the narrative unfolds, the character of Mollie Kyle, played by Lily Gladstone, undergoes a transformation from avenging angel to passive victim. Her diminishing presence in the second half of the story leaves a dramatic void, raising questions about the film’s overall impact.

While Killers of the Flower Moon carries the stamp of Scorsese’s craftsmanship, it doesn’t seamlessly align with his lofty moral ambitions. Unlike his earlier crime epics, the film shifts its focus to an objective vantage, emphasizing the plight of the Osage over the nefariousness of the antagonists. The absence of the FBI investigation perspective, a significant element in David Grann’s book, raises eyebrows, hinting at an editing process that may have sacrificed crucial elements.

Scorsese’s investment in lost history and the manipulation of public record is evident throughout the film. The use of newsreels and photographs serves as a reminder of the precariousness of collective memory, emphasizing how official histories are often shaped by commercial image-makers. The film plays out like a vignette-driven history, eschewing frivolous dramatic beats for a serious exploration of its subject matter.

Every actor brings their A-game, with DiCaprio delivering a charmingly tragic portrayal, Gladstone exuding stoic indigence, and De Niro offering committed and detailed screen work reminiscent of his earlier roles. The film concludes with an extraordinary coda, a quintessential Scorsese touch that laments and praises the transformation of history into mass entertainment.

On first impression, Killers of the Flower Moon emerges as a good but uneven film. It grapples with the weighty themes of exploitation, greed, and historical manipulation, yet its structural choices and character dynamics leave room for critique. While not an unequivocally great film, it stands as a testament to Scorsese’s dedication to giving voice to the victims and confronting the shadows of America’s past.